UNDERSTANDING CHOLANGIOCARCINOMA

Cholangiocarcinoma, pronounced (koh-LAN-jee-oh-KAR-sih-NOH-muh), is a rare bile duct cancer of the liver.

MORE INFORMATION

With approximately 10,000 cases a year being diagnosed in the United States, cholangiocarcinoma is the second most common primary liver cancer in the world. We’ve provided resources to help.

CCF offers both an infographic and physician tear off to help you navigate your journey.

Click below to download each PDF.

Overview

What is cholangiocarcinoma?

Cholangiocarcinoma starts in the bile duct, a thin tube, about 4 to 5 inches long, that reaches from the liver to the small intestine. The major function of the bile duct is to move a fluid called bile from the liver and gallbladder to the small intestine, where it helps digest the fats in food.

Different parts of the bile duct system have different names. In the liver it begins as many tiny tubes (ductules) where bile collects from the liver cells. The ductules come together to form small ducts, which then merge into larger ducts and eventually the left and right hepatic ducts. The ducts within the liver are called intrahepatic bile ducts. These ducts exit from the liver and join to form the common hepatic duct at the hilum.

About one-third of the way along the length of the bile duct, the gallbladder (a small organ that stores bile) attaches by a small duct called the cystic duct. The combined duct is called the common bile duct. The common bile duct passes through part of the pancreas before it empties into the first part of the small intestine (the duodenum), next to where the pancreatic duct also enters the small intestine.

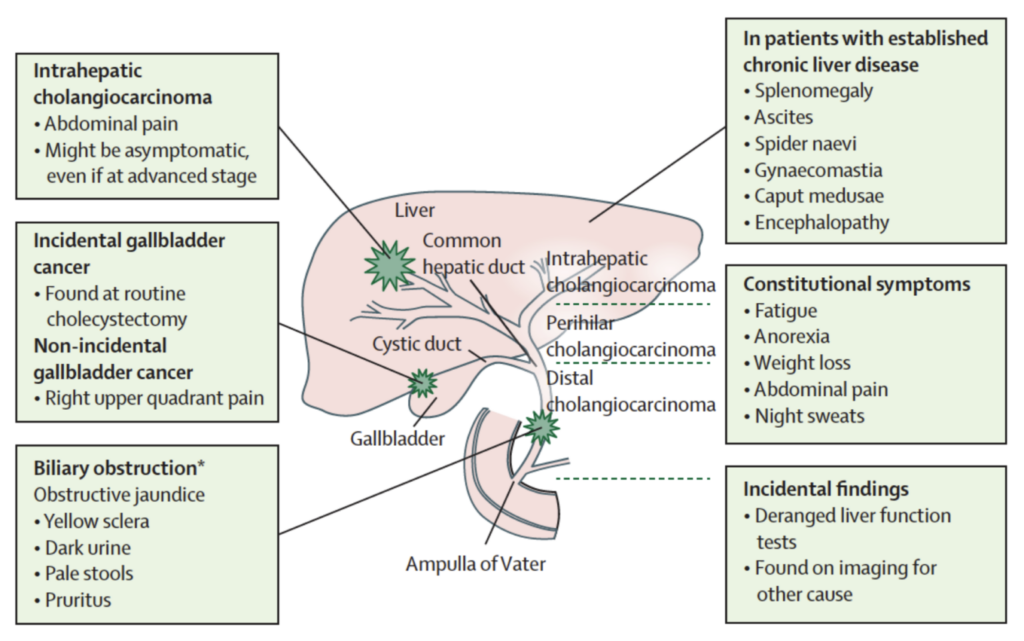

Cancers can develop in any part of the bile duct and, based on their location, are classified into 3 types:

- Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma

- Perihilar cholangiocarcinoma

- Distal cholangiocarcinoma

Intrahepatic CCA occurs inside the liver where cancer develops in the hepatic bile ducts or the smaller intrahepatic biliary ducts. In some cases, intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma tumors may have microscopic features of both hepatocellular carcinoma (liver cancer) and cholangiocarcinoma (bile duct cancer) and are considered “combined” or “mixed” tumors.

These cancers develop where the right and left hepatic ducts have joined and are leaving the liver. These are the most common type of cholangiocarcinoma accounting for more than half of all bile duct cancers.

Distal CCA occurs outside the liver after the right and left hepatic bile ducts have joined to form the common bile duct. This type of cancer is found where the common bile duct passes through the pancreas and into the small intestine.

Key Statistics

Key Statistics

- About 10,000 people in the United States develop cholangiocarcinoma each year.

- Cholangiocarcinoma is much more common in Asia, mostly because of a common parasitic infection of the bile duct.

- Almost 2 out of 3 people with cholangiocarcinoma are 65 or older when it is found.

- The average age of people diagnosed with cancer of the intrahepatic bile ducts is 70.

- The average age of people diagnosed with cancer of the extrahepatic bile ducts (perihilar or distal cholangiocarcinoma) is 72.

- The chances of survival for patients with bile duct cancer depend to a large extent on its location and how advanced it is when it is found. It also may depend on access to innovative treatments such as clinical trials. Clinical trials offer access to therapies that may not be available through standard care, potentially providing patients with more effective options to combat the disease.

Adapted from the American Cancer Society

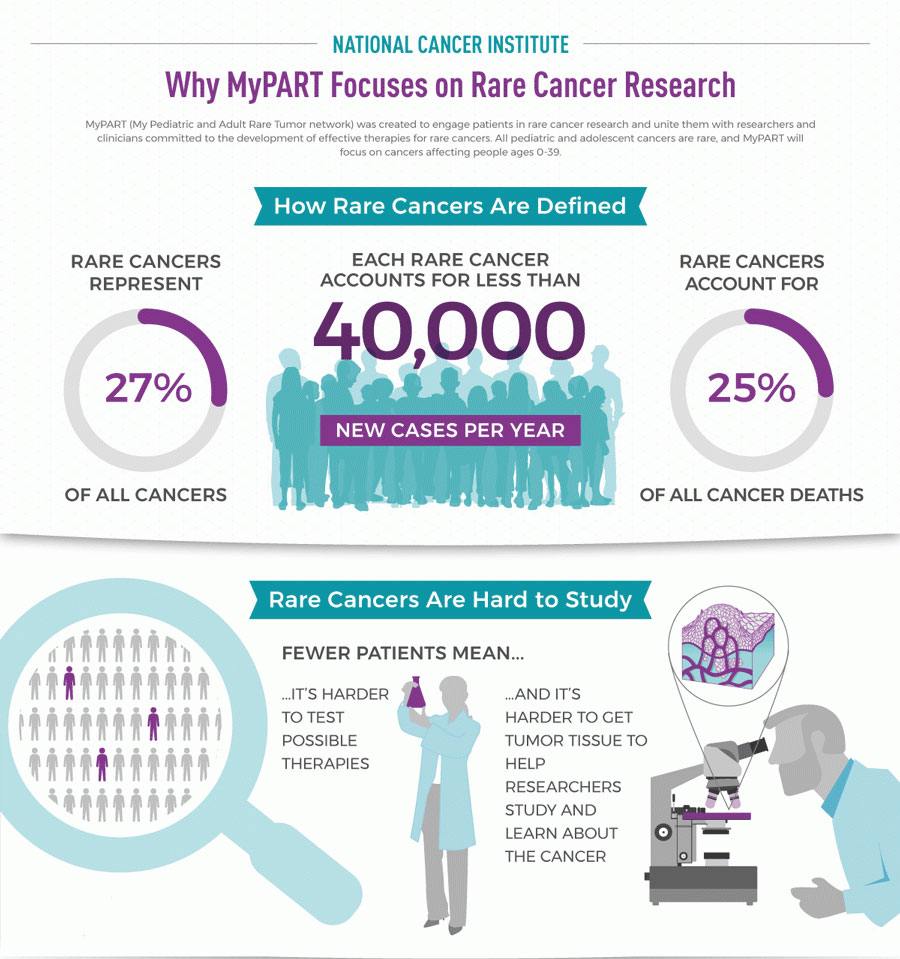

About Rare Cancers

Why is cholangiocarcinoma considered a rare cancer?

Rare cancers are those that affect fewer than 40,000 people per year in the U.S. As a group, they make up just over a quarter of all cancers.

Rare cancers are challenging for patients, doctors, and scientists.

For patients:

- It often takes a long time from the time you think something is wrong to the time when doctors know that you have a rare cancer and what kind of cancer it is.

- It is hard to find doctors who know a lot about your cancer and how to treat it.

- It is hard to know what to do when doctors don’t agree on how to treat your cancer.

- You may need to travel far from your home and family to get treatment for your rare cancer.

For doctors:

- You may not know what to tell your patient about what to expect with their rare cancer.

- You may not have been trained in how to treat this type of rare cancer.

- It is hard to find an expert in the rare cancer who can answer questions or to whom you can refer your patient.

For scientists:

- There may be no information about the rare cancer to give you ideas on which drugs could treat it.

- There may be no animal or cell models of the rare cancer in which to test your ideas.

- There may not be enough tumor samples from rare cancer patients available for your research.

- If you have an idea of a drug that could treat the cancer, it may be hard to find enough patients with the rare cancer to test your idea.

Adapted from cancer.gov

Risk Factors

DISEASES IN THE LIVER OR BILE DUCTS:

A condition in which inflammation of the bile duct (cholangitis) leads to the formation of scar tissue (sclerosis) and an increased risk of cholangiocarcinoma. The cause of the inflammation is not usually known. Many people with this disease also have inflammation of the large intestine called ulcerative colitis.

Liver fluke infections occur in some Asian countries when people eat raw, pickled, fermented or poorly cooked fish that are infected with tiny parasitic worms.

- In humans, these flukes live in the bile ducts and usually don’t cause any symptoms. Previous studies showed that around 10% of chronically infected patients with these parasites will develop cholangiocarcinoma.

- There are several types of liver flukes. The ones most closely related to cholangiocarcinoma risk are called Clonorchis sinensis and Opisthorchis viverrini.

- Liver fluke infection is rare in the US but can affect people who travel to Asia, like Vietnam War veterans.

Visit https://www.scops.org.uk/internal-parasites/liver-fluke/ for more information.

Long term infection with either hepatitis B virus or hepatitis C virus increases the risk of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. This may be at least in part due to the fact that infections with these viruses can also lead to cirrhosis. Learn more at https://www.epainassist.com/abdominal-pain/liver/viral-hepatitis

Cirrhosis is a condition in which the liver does not function properly due to long-term damage. This damage is characterized by the replacement of normal liver tissue by scar tissue. Typically, the disease develops slowly over months or years. Early on, there are often no symptoms. Learn more at https://liverswithlife.com/stages-of-liver-disease-overview/

Bile duct stones are similar to, but much smaller than gallstones, which can also cause inflammation that increases the risk of cholangiocarcinoma. Learn more at https://www.kediamd.com/everything-you-want-to-know-about-bile-duct-stones/

These abnormalities can allow digestive juices from the pancreas to reflux (flow back “upstream”) into the bile ducts. This backward flow prevents the bile from being emptied through the bile ducts as quickly as normal. People with these abnormalities are at higher risk of cholangiocarcinoma.

Choledochal cysts are bile-filled sacs that are connected to the bile duct. The cells lining the sac often have areas of pre-cancerous growth, which can increase the risk for developing cholangiocarcinoma.

- It is a rare congenital abnormality. In the International Cholangiocarcinoma Patient Registry, only 2.2% of patients have been diagnosed with choledochal cysts.

- It is more common in Asian females.

- For patients with choledochal cysts, the average age at diagnosis is 32, which is much younger than the average cholangiocarcinoma patient.

- A recent analysis of SEERs data showed that patients with choledochal cysts have approximately 16 times higher risk for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma and 27 times higher risk for extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma.

Petrick JL, Yang B, Altekruse SF, et al. Risk factors for intrahepatic and extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States: a population‐based study in SEER‐Medicare. PLoS One. 2017;12(10):e0186643.

Soreide K, Korner H, Havnen J, Soreide JA. Bile duct cysts in adults. Br J Surg. 2004;91(12):1538‐1548.

Two other rare diseases can lead to cholangioarcinoma in some cases, including polycystic liver disease and Caroli syndrome (a dilation of the intrahepatic bile ducts that is present at birth).

A recent study showed that patients with Caroli’s disease have approximately 38 times higher risk for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma and 97 times higher risk for extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma compared to general population.

OTHER RISK FACTORS INCLUDE:

Older people are more likely than younger people to get cholangiocarcinoma.

Almost 2 out of 3 people with cholangiocarcinoma are 65 or older when it is found.

- The average age of people diagnosed with cancer of the intrahepatic bile ducts is 70.

- The average age of people diagnosed with cancer of the extrahepatic bile ducts (perihilar or distal cholangiocarcinoma) is 72.

People who drink alcohol are more likely to get intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. The risk is higher in those that have liver problems from drinking alcohol.

Studies have reported that if you have more than 5-6 drinks per day, you have a 2-3 times higher risk for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. The International Cholangiocarcinoma Patients Registry shows that 65% of cholangiocarcinoma patients drink alcohol, with 7% drinking more than 3 drinks a day.

Palmer WC, Patel T. Are common factors involved in the pathogenesis of primary liver cancers? A meta‐analysis of risk factors for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J Hepatol. 2012;57(1):69‐76.

The data from many different studies show that people with diabetes have a slightly higher risk of cholangiocarcinoma than the general population.

Being overweight or obese can increase the risk of developing cancers of the gallbladder and bile ducts. This could be because obesity increases the risk of gallstones and bile duct stones. It remains unclear why obesity can increase the chance of cholangiocarcinoma developing.

Is Cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) Inherited?

Most cholangiocarcinomas are not found in people with a family history of the disease; however, it can

sometimes be linked to an inherited gene. This means that certain genetic factors passed down from

your family can increase your risk of developing this cancer. Researchers have found that some people

with CCA have specific gene mutations that can be inherited from their parents. How often this happens

is not known exactly, but it ranges from 5% to 16%, depending on different studies.

What inherited syndromes are associated with an increased risk of cholangiocarcinoma?

Inherited cancer syndromes associated with an increased risk of cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) include:

Lynch Syndrome (Mismatch Repair Deficiency): This syndrome is typically associated with an

increased risk of colorectal cancer but can also elevate the risk of developing CCA.

Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer Syndrome (BRCA1/2 Mutations): While primarily

linked to breast and ovarian cancers, mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes have been found in

some patients with CCA.

BAP1 Tumor Predisposition Syndrome: This syndrome is related to mutations in the BAP1

gene, which can increase the risk of various cancers, including CCA.

Homologous Recombination Repair Deficiency (HRD): This condition, involving mutations in

genes responsible for DNA repair, is also linked to a higher risk of CCA.

These syndromes affect genes that are crucial for DNA repair and cell cycle regulation, which can lead to

an increased susceptibility to developing cancers, including CCA.

How Do I Know If I May Have an Inherited Cholangiocarcinoma?

You might be at a higher risk of having an inherited form of CCA if you have a family history of cancers,

especially biliary tract cancers or certain types of breast, ovarian, or colorectal cancers. Specific gene

mutations, like those in BRCA1 or BRCA2, which are often linked to breast and ovarian cancers, have

also been found in people with CCA. Additionally, some ethnic groups, such as those of Asian descent,

may have a higher prevalence of these genetic mutations.

What Should I Do If I Think I Have an Inherited Cholangiocarcinoma?

If you suspect you might have inherited CCA due to a family history of cancer or other risk factors, it’s

important to talk to your doctor. They may suggest genetic testing to see if you have any of the mutations

linked to CCA. Even though there aren’t specific guidelines for testing everyone with CCA, knowing your

genetic status can help guide treatment decisions and may also provide important information for your

family members. Genetic counseling can also help you understand your risk and the steps you can take

to manage it.

How can I help to advance the knowledge of inherited cholangiocarcinoma?

You can help by getting involved in a study that is open to everyone, patients and non-patients, whether or not there may be an inherited link in your family. This will help researchers learn more about inherited genes involved in cholangiocarcinoma, which may help the next generation.

Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) includes ulcerative colitis (a chronic condition which results in inflammation and ulcers in the colon and rectum) and Crohn’s disease (a chronic condition which results in inflammation and ulcers along the gastrointestinal tract extending from the mouth to the anus).

Both conditions lead to chronic inflammation and/or changes in the intestinal microbiome and could lead to cholangiocarcinoma.

People with these diseases are around 3 times more likely develop intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma and 2 times more likely to develop extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. A stronger association between intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma and ulcerative colitis was reported compared to patients with Crohn’s disease.

A radioactive substance called Thorotrast (thorium dioxide) was used as a contrast agent for x-rays until the 1950s and can lead to cholangiocarcinoma, as well as to some types of liver cancer. Although it is no longer used, it has been shown to cause cancer 16-45 years after use.

After injecting Thorotrast, it is accumulated in the liver, spleen, bone marrow cells and could result into several different types of cancer including cholangiocarcinoma, as well as other cancers of the liver.

Previous studies showed that Thorotrast increases the risk of cholangiocarcinoma by 300 times more than general population.

Studies have found that several other risk factors may increase the risk of cholangiocarcinoma, but the link between these risk factors and cholangiocarcinoma is not as clear.

They include:

- Smoking

- The mechanisms by which smoking cause cholangiocarcinoma is unclear, however, this could be because tobacco has many substances that can cause cancer and these substances accumulated in the liver cells and secreted into the bile

- Two previous studies showed that smoking associated with 1.5 time increase in the risk of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma

- Another study reported increase in the risk of extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in smokers compared with non-smokers

- Pancreatitis (inflammation of the pancreas)

- Inflammation of the pancreas leads to narrowing of the biliary channels in 3%‐23% of patients, which in turn may increase the risk of biliary channel inflammation and stone formation that are risk factors for cholangiocarcinoma development

- A positive association between chronic pancreatitis and CCA has been reported, with a 7 time increase risk of extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma development and 3-times increase risk of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma development

- Infection with HIV

- Exposure to asbestos

- Recently, two different case‐control studies reported an increase risk of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma with asbestos exposure. But, there is a limited evidence for extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Similar results have been confirmed in a Nordic population‐based study

- Exposure to radon or other radioactive chemicals

- Exposure to dioxin, nitrosamines, or polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs)

- Although there is an association between these factors and increased risk of different types of cancer, there is a limited amount of data about the association between these factors and the risk of cholangiocarcinoma development

Petrick JL, Yang B, Altekruse SF, et al. Risk factors for intrahepatic and extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States: a population‐based study in SEER‐Medicare. PLoS One. 2017;12(10):e0186643.

Petrick JL, Campbell PT, Koshiol J, et al. Tobacco, alcohol use and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: the liver cancer pooling project. Br J Cancer. 2018;118(7):1005‐1012.

Ye XH, Huai JP, Ding J, Chen YP, Sun XC. Smoking, alcohol consumption, and the risk of extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: a meta‐analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19(46):8780‐8788.

Petrick JL, Yang B, Altekruse SF, et al. Risk factors for intrahepatic and extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States: a population‐based study in SEER‐Medicare. PLoS One. 2017;12(10):e0186643.

Brandi G, Di Girolamo S, Farioli A, et al. Asbestos: a hidden player behind the cholangiocarcinoma increase? Findings from a case‐control analysis. Cancer Causes Control. 2013;24(5):911‐918.

Farioli A, Straif K, Brandi G, et al. Occupational exposure to asbestos and risk of cholangiocarcinoma: a population‐based case‐control study in four Nordic countries. Occup Environ Med. 2018;75(3):191‐198.

Adapted from National Institutes of Health: http://www.cancer.gov/

Symptoms

- Chills

- Clay-colored stools

- Dark urine

- Fatigue

- Itching (pruritus)

- Loss of appetite

- Nausea

- Pain in the upper right abdomen that may radiate to the back

- Weight Loss

- Yellowing of the skin (jaundice)

Cancer in different areas may cause different symptoms.

Staging

After a person is diagnosed, doctors will try to figure out if it has spread, and if so, how far. This process is called staging. The stage of a cancer describes how much cancer is in the body. It helps determine how serious the cancer is and how best to treat it. Doctors also use a cancer’s stage when talking about survival statistics.

Although each person’s cancer experience is unique, cancers with similar stages tend to have a similar outlook and are often treated in much the same way.

How is the stage determined?

The staging system most often used is the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM system, which is based on 3 key pieces of information:

- The extent (size) of the main tumor (T): How large has the cancer grown? Has the cancer reached nearby structures or organs?

- The spread to nearby lymph nodes (N): Has the cancer spread to nearby lymph nodes?

- The spread (metastasis) to distant sites (M): Has the cancer spread to distant lymph nodes or distant organs such as the bones, lungs, or peritoneum (the lining of the abdomen )?

Numbers or letters after T, N, and M provide more details about each of these factors. Higher numbers mean the cancer is more advanced.

Once a person’s T, N, and M categories have been determined, this information is combined in a process called stage grouping to assign an overall stage. For more on this, see Cancer Staging.

Cancer staging can be complex, so ask your doctor to explain it to you in a way you understand.