Roller Coaster - Barry Cohen's Story

Written by Cait with edits of style and flair by Barry Cohen

Depending on your perspective, roller coaster might have a negative connotation. For Barry Cohen though, it doesn’t, and that’s in no small part because he chooses for it to be positive. Speaking with him for this feature was both entertaining and informative, and I’m delighted to share his story here. We’ll start with a recap of his path so far then end with what he referred to as ‘nuggets’ that he imparted throughout our chat.

Barry’s Story

As is not uncommon with our disease, then 50 year-old Barry was asymptomatic before his diagnosis. In October, 2014 he went to see his primary care physician for a routine physical when the bloodwork came back suggestive of possible diabetes. He was prescribed metformin and told to come back in three months. Later, when his blood work didn’t indicate a good response, Barry’s PCP ordered a CT scan and then an MRI which showed an area of concern outside of his liver. He was referred to a local GI doctor who performed an ECRP to obtain a sample of a 8 cm mass in his bile duct that was pressing against his inferior vena cava. Unfortunately, a day later, he developed pancreatitis that required more procedures and a hospital stay, and the word ‘cancer’ was spoken.

Having strong ties in NYC stemming from a successful career in finance, Barry immediately began reaching out to the Big Apple’s major medical institutions, understanding even from the beginning that their expertise would be needed to handle a disease as rare and complex as cholangiocarcinoma. First, Barry headed to Memorial Sloan Kettering to meet with an oncologist and a surgeon.

Here, he encountered his first dose of cholangiocarcinoma reality – even the experts are divided on which steps to take. Neither thought he was a surgical candidate, but both thought that if they could shrink the tumor, it might enter the realm of possibility. One advocated the new, and at that time fairly experimental, HAI pump, while the other recommended some newer trial chemotherapy.

Lacking a medical consensus on an obvious next step, and still not willing to relinquish his hope for surgery first, Barry headed across town to Columbia Medical Center. There he met with a department head who agreed that surgery would be complicated, but suggested that Barry see a specific surgeon with transplantation experience and a reputation for taking challenging cases. When Barry met with the surgeon, he finally heard what he had been hoping for: surgery was possible and this surgeon was willing to take the chance if Barry was.

The decision was dramatic, literally life and death, but Barry’s subsequent evaluation of what to do was calculated:

- He asked his surgeon for odds, understanding it is a small sample size and not highly reliable, and that the opinion was based on imaging and not an internal view of the entire picture. The surgeon put the approximate odds at 10% Barry would not survive the surgery, 35% he would be cured, and 55% the cancer would come back. The oncologist and another surgeon at Columbia agreed with this, their primary concern being recurrence

- He revisited the MSK doctors who were somewhat surprised that Barry was considering bypassing their shrinkage suggestions and put his approximate odds at 30% he would not survive the surgery, 20% he would be cured, and 50% it would come back.

- He consulted a close friend, who is a defense attorney, and asked for unusual counsel around what he should do. Barry knew this person to be discerning in weighty matters as he regularly has to advise clients facing long penal sentences on whether they should take a plea or risk going before a jury. Barry credits this friend with helping to solidify his ultimate decision to go forward with the surgery.

After a month of reflection from the original diagnosis, Barry felt clear-headed. He had mastered his emotions, approached the problem with logic, and had consulted experts who could offer all of the insights he needed to make the best decision for him. Before surgery came, however, he had one more challenge, how to explain what was happening to his 15 and 18 year-old children.

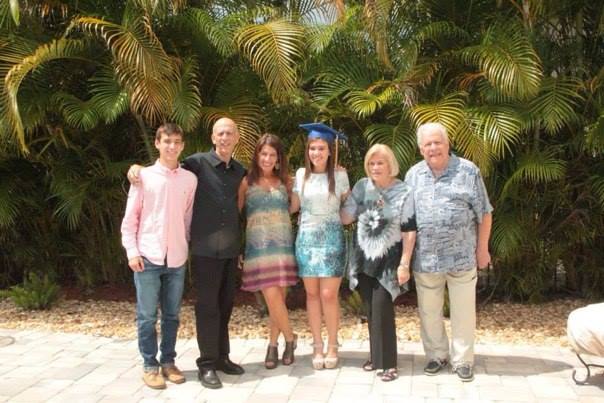

Barry pictured far right with his family on the 4th of July, 2017

He met with his rabbi and asked for his thoughts on how to approach this conversation. The rabbi spoke with kindness and candor. He said Barry needed to be honest, to not say everything would be fine, and to share with them what the doctors had said. He said that like everything else with cancer treatment, this critical communication came with a gamble. If Barry told them he was going to be fine and everything went as they hoped, then he had the chance to spare his children the concern of facing his mortality. If the unthinkable happened, however, and the children were not prepared, the psychological fallout would be much worse.

Concerned with his son’s ability to grasp the probability, Barry called a family meeting and brought with him a deck of cards. He explained the pending surgery to his children who seemed to comprehend the complexity. Then, he discussed with them the odds of his survival. Seeing his son’s confusion, he pulled out the deck of cards. “There are four aces in a deck of cards, right?” he said to his children, who nodded. He then turned to his son, fanning the deck in front of him. “There are no guarantees in life or with this surgery. The odds of picking an ace are similar to that of me not making it. Go ahead and pick one,” he directed. His son hesitated and then drew a card. They all smiled widely when they saw it was a king. He then turned to his daughter, who reached for her turn, and pulled out a three. Delighted, she squeezed her card close to her heart. Barry then turned to his wife, whose nerves at this point were shot. She gave him a dark look and firmly stated, “Put the deck away!” He chuckled and complied, satisfied that he had accomplished what he needed to for his children with the exercise.

The morning of his surgery, Barry stopped along the East River and stared out over the salty water. As was his custom when the stakes were high (like the day he got married), he squared up and drove a golf ball far out into its depths. His mind, which had spent the previous night in a restless state, was now at ease, and he headed to the hospital. When he arrived, his surgeon asked about the golf club. When Barry explained this habit, the surgeon grinned and said he understands those sorts of rituals. He himself had braved New York City traffic and rode his bike to the hospital that morning. They were a good pair for the battle ahead.

The surgery was indeed complicated, but Barry’s surgeon, having experience in liver transplants, was able to navigate the complex vasculature with his team for over six hours. When Barry awoke and for the next day or so, he was ecstatic to find himself still among the living. He was so overjoyed, in fact, that the entirety of his medical team attributed his mental wellness to a remarkable initial recovery, and moved him out of the ICU and adjusted his meds a little too quickly. When his health quickly declined, they brought him back to the ICU. During a visit several days later after he had become stabilized, his doctors joked that they had had patients fool one of them before, but not the entire team. Barry smiled and told them he had just been so grateful to be alive, that everything else seemed small.

After 18 days in the hospital, Barry stayed at friends’ house for ten days. The husband is a doctor and was able to aid in changing Barry’s bandages, helping him understand what his body was going through, making him laugh, and had him putting golf balls on his patio and the golf course. The wife worked from home, was a great cook, reminded him to take his 23 daily pills, and welcomed and charmed his visitors. They were the perfect, firm caregivers for him and he credits the two of them with the rapid improvement he experienced so soon after his time in the hospital. As a result, he was able to reduce his medication to only five daily pills and made it home by Mother’s Day and his daughter’s graduation in May, 2015, which was an important objective for him.

Barry, second from the left, celebrating his daughter’s graduation in May, 2015.

Even though his margins were deemed clear, he consented to adjuvant chemotherapy consisting of a gem/cis combo. Additionally, his Foundation One report did not offer practical immunotherapy solutions. While his scans were clear of cancer for a year and a half, his life was not without medical complications. He had a large incisional hernia, but he had to wait six months to have it addressed because his team found a blood clot in his vena cava in one of his follow up scans, which needed to resolve with the aid of blood thinners. None of the hurdles were remotely small, but Barry’s attitude throughout stayed largely positive in part because that is his nature, and in part because he was just grateful there was no cancer.

In December, 2016, however, he received the words that we dread: there were three new small spots in his liver, and his medical team recommended chemoembolization. He remembers the procedure well as he was intentionally kept awake. He left the hospital that day feeling well and the interventional radiologist deemed the procedure a success as the spots were eradicated. However, shortly thereafter he developed a liver infection that required more procedures and a week-long hospital stay. He needed an external biliary drain, which he still has a year later.

When three additional spots materialized in April, 2017, he sought out the opinion of a top oncologist at M.D. Anderson. He has options, but for now he’s on a maintenance regimen of Xeloda. If the cancer begins to grow again or new spots appear, he will explore the alternatives.

Barry sees his mission now as to try and live another three years. If he is fortunate enough to accomplish that, he will try to tack on several more. He concedes that he’s not likely to live to see 75, but he said he has peace with that, and he is grateful for the time he’s already been given. He desires to see his children a little more settled into adulthood, to see a business project (a labor of love) through to completion, and to help other patients, all of which has motivated him to adopt a healthy lifestyle. He also stressed the choices that we have, noting that cancer is out of our control, but so much of the experience around the disease is in our control, and the choices we make can help give us more time. “We can’t control the wind, but we can control the sails.”

Barry, at a concert with his daughter, enjoying music, one of his many sources of comfort.

Throughout our hour and a half on the phone together, Barry imparted wisdom in the form of ‘nuggets’, short vignettes tied into his journey that he would pause to espouse then continue with his story. Now that you know a little about Barry, we can better enjoy and appreciate these insights, captured below:

- Most local or small town doctors mean well, but they are out of their depth with cholangiocarcinoma. We, as patients, need to seek out the experts, and the CCF website and Facebook support group are excellent resources. Have a thirst for increasing knowledge and be open to alternative ideas.

- Similar to the above, it’s important to even have the small procedures like ECRP’s and scans conducted at major centers if possible as they are better versed in employing these tactics in systems impacted by cancer. They may want to redo scans since their equipment is typically better.

- Patients who are interested in surgery should send all their medical information and go to see surgeons themselves for opinions on whether or not they are candidates. Furthermore, he cited his experience with a transplant surgeon as improving his odds based on the doctor’s knowledge of the complex vasculature involved in liver and bile duct anatomy.

- Doctors don’t always tell the absolute truth. Barry made a point that doctors are human, and sometimes hubris can make them over-promise when they want a patient to stay and choose their course of action. Also, each doctor, department head, and hospital has their own comfort level and set of guidelines for taking on risk. Their comfort or willingness to take on risk may not match with your best possible outcome.

- Medicine in America is a commodity, and in this business, we are big ticket customers. Sometimes we may feel swallowed up by the system, but doctors and hospitals stand to make a lot of money off of us, and that fact should empower us to be our own advocates.

- If we’re still struggling to be assertive, find a proxy and have them flex some muscle. It’s not in everyone’s nature to be firm, but that tenacity is sometimes needed in navigating modern medicine.

- Not everyone is a natural caregiver. We might expect our spouse, parent, children, or person closest to us to care for us, but that is not everyone’s strength. It might be unfair to ask to put the caregiver mantel on one who isn’t wired for it. Here again, we need to seek out people in our lives who are best suited for this role, and engage them accordingly.

- Give yourself deadlines to make decisions and keep to them. He suggested a few weeks of reflection either way when making weighty decisions to give time to get emotions into check and let logic guide the decision. However, do not let the window of an option of surgery to slip away.

- Find someone in your life that can unemotionally help you with decisions. There are many professions that employ these high stakes evaluations, and if we can find one of those individuals, their experience can help navigate the most significant choices and treatment plans.

- Do what you can to manage your health. Barry called out that he found tremendous success in his career by his mid to late 30’s, but he knows now that the cost was some of his health. Eat well, exercise often, reduce stress, listen to music, surround yourself with beautiful views and pictures, be positive, have hope, visualize the tumor shrinking and seeing a healthy you in the mirror, and eliminate all negative people (even if they are close to you) and influences. “The immune system is like an army. Armies fight wars. Make no mistake, we are engaged in a war. A war with cancer. We need to strengthen the army to stop the progression of cancer.”

- Maintain human interaction and don’t neglect your psychological health as it correlates to longer survival and a better quality of life.

Thank you so much Barry for your time and for this wisdom. His only ask was that we dedicate this post in memory of his late cousin by marriage and fellow cholangiocarcinoma patient, Derin Hampton. Derin touched many lives with his humor, never ending hope, and his humanity. He helped Barry and others immeasurably on the CCF website and elsewhere in learning to cope, and with inspiration, including his son that is currently studying for a career in the medical profession.

http://www.legacy.com/obituaries/heraldtribune/obituary.aspx?pid=186756356

Pictured: Derin Hampton, beloved cholangioarcinoma mentor and friend

Stay tuned next week for Andy Tebbut’s story in the second of three patient perspectives leading up to the Cholangiocarcinoma Foundation’s annual conference in Salt Lake!